October 2, 2017

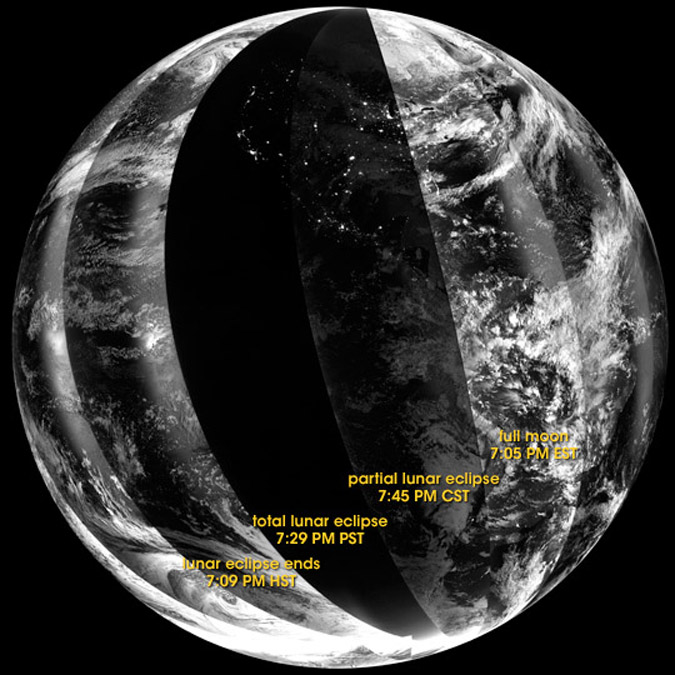

A Global Eclipse

Originally published March 21, 2008

image from NASA Earth Observatory Newsroom

Eclipses of the Moon are probably the most common celestial spectacle, one that all LPOD viewers have seen, as have billions of people from their tribal villages or downtown skyscraper roofs. But have you seen one from space? The image above is a clever assemblage of weather satellite images that capture both the temporal and geographical ebb and flow of the lunar eclipse of last February 20. The images come from a Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP) satellite in a 102 minute polar orbit. Each of the gores - or image segments - was taken during a different orbit of the satellite. If the 102 minute orbital period and the 40 minute difference in time between the first two labeled passes seems confusing, notice - as I originally didn't - that the 7:05 pass is EST and the 7:40 one is CST - different time zones. And the DMSP satellite takes a series of images, not just one, on each side of the orbit, so the difference can be more or less than 102 minutes. Because all the images are taken after sunset the clouds and surface (do you see South America?) are illuminated by full Moon light. The rightmost images are before the eclipse and are well illuminated. The 7:45 PM image was acquired during the penumbral stage so the image is dark because of the reduced illumination. By the time of the 7:29 PM PST image over the western US, it eclipse had reached totality, and there was too little Moon light to show natural features, only the lights of cities are visible. The western most images were taken after the eclipse, and again show bright clouds. It is fascinating to look at a higher resolution version of the image (5.4 MB) to see the wispy clouds and city lights in the 7:45 PM segment - its almost like scanning a galactic scene with nebular clouds and stars.

Chuck Wood

Technical Note

Image and data processing by NOAA’s National Geophysical Data Center, Earth Observation Group, Boulder, CO

Yesterday's LPOD: A Step Closer To Solving the Riddle of Lunar Water

Tomorrow's LPOD: Another Megadome

COMMENTS

(1) Was this image taken in the infrared? I used to look at GOES satellite imagery taken around the time of local sunset, and, in those, you could detect nighttime cloud cover only in the infrared -- not in the visible bands. Maybe I never looked at Full Moon, or maybe the newer cameras are just more sensitive? Does the nighttime Earth look different at different wavelengths, or is it just dimmer in the visible? Also, the Apollo 12 astronauts, who enjoyed a relatively distant view of the nighttime Earth (with the Sun hidden behind it) on their way back from the Moon, were much more impressed by lightning storms than by city lights (which they found tiny and hard to see). That would have been Nov. 24, 1969, with an almost perfect Full Moon. Are there any thunderstorms here?

-- Jim

(2) Jim - Apparently the DMSP has two imaging systems, one working at .4 to 1.1 micron and the other infrared one at 10 microns. This image is from the vis-near-IR camera because it uses Moonlight for illumination. The image was taken with a new model of DMSP satellite launched in 2003 that was an upgrade, which may include detectors with greater sensitivity. The IR sensor would see right through the shadow to the clouds and surface.

I bet the Night Sky Association has real data but I imagine city light brightness has greatly increased since Apollo. I don't see any lightning in the image above but there may be some over the Amazon in the high res version.

Jim - didn't you mention once that a Lunar Orbiter imaged an eclipse - can you remind me of the details?

Thanks,

Chuck

(3) Chuck,

Thanks for the extra information.

Lunar Orbiter may have imaged the Earth, but not during an eclipse (as far as I know). It is Surveyor III, the lander visited by the Apollo 12 astronauts, which was able to grab some images of a lunar eclipse as seen from the Moon on April 24, 1967. This was the subject of one the LPOD's that appeared while you were away at the LPSC.

The Surveyor III images were taken with a zoomable video camera designed for looking at the surrounding soil and horizon through a variety of filters. This camera, like all those on Surveyors, looked up through a kind of periscope mirror and was not expected to be able to look high enough in the sky to see the Earth. But by chance it landed on a rather steeply inclined surface in Surveyor crater, and the Earth was just barely visible by tipping the mirror to the extreme limit of its designed tilt. However, it was apparently not possible to use anything but the minimum zoom at that angle. Hence the photos are very small and "grainy". Kaguya's HDTV could undoubtedly do much better, but the Earth's atmosphere (where the reddish light of the eclipse originates) is a mere 10-20 km thick, which as we know from looking at the Moon from Earth is not something you can see well with the naked eye at that distance. You would need a reasonably powerful telescope to resolve it. I don't think even Kaguya's Terrain Mapping Camera (if pointed towards Earth) could quite do the job, but it could certainly return some fascinating images.

By the way, the dark side of the Earth visible in the Surveyor III images is centered on the mid-Pacific, but Australia, Japan and California would be visible around the edges (the references cited in the LPOD contain detailed maps and other information). I can't see any city lights, but neither the resolution nor the exposure time were probably sufficient to show them. And even in those pre-internet days, pages 52-56 of the July 1967 issue of Sky and Telescope published photos taken looking back at the eclipsed Moon from California at almost exactly the time of the Surveyor photos -- so one can see exactly how deep a shadow the Surveyor III site was in.

There is a bit more about this on the Cloudy Nights Lunar Observing Forum, and a nice page bringing together views of the shadows cast by and on the Moon here.

-- Jim

COMMENTS?

Register, Log in, and join in the comments.