Difference between revisions of "January 23, 2008"

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

<!-- ws:start:WikiTextHeadingRule:0:<h2> --> | <!-- ws:start:WikiTextHeadingRule:0:<h2> --> | ||

<!-- ws:start:WikiTextLocalImageRule:2:<img src="/file/view/LPOD-23Jan-08.jpg/34852125/LPOD-23Jan-08.jpg" alt="" title="" /> -->[[File:LPOD-23Jan-08.jpg|LPOD-23Jan-08.jpg]]<!-- ws:end:WikiTextLocalImageRule:2 --><br /> | <!-- ws:start:WikiTextLocalImageRule:2:<img src="/file/view/LPOD-23Jan-08.jpg/34852125/LPOD-23Jan-08.jpg" alt="" title="" /> -->[[File:LPOD-23Jan-08.jpg|LPOD-23Jan-08.jpg]]<!-- ws:end:WikiTextLocalImageRule:2 --><br /> | ||

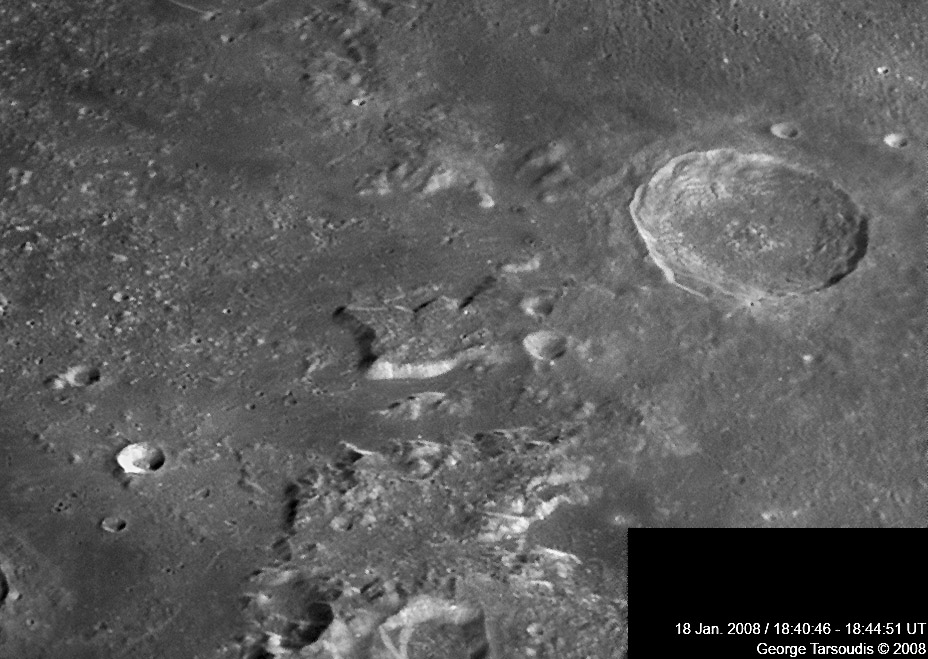

| − | <em>image by [mailto:g.tarsoudis@freemail.gr | + | <em>image by [mailto:g.tarsoudis@freemail.gr George Tarsoudis], Alexandroupolis, Greece</em><br /> |

<br /> | <br /> | ||

Nearly every piece of lunar terrain was formed by impact or volcanism, and has been modified by one or both of these processes. But the 50 km long, steep-sided plateau west of Eudoxus is strangely different from most impact and volcanic landforms. This is the northern end of the Caucasus Mountains and so is related to impact because it is apparently part of the rim of the Imbrium Basin. There appears to be a general lowering of topography toward Laméch, the 13 km crater at the eastern end of the plateau, consistent with it being ejecta on top of an uplifted rim. But what sculpted the sharply-defined sides of the plateau? It's possible (but just speculation) that the slightly curved western end is all that remains of a steeply-dipping crater such as Calippus, shown at the bottom edge of the image. The bright, south-facing scarp is similar to, and parallel to, the many faults that cut the Apennines and Caucasus. The hidden north side is more complex, bearing two straight-edged notches. I suppose this distinctive feature is really just an ejecta/rim block, and its peculiarity is due to its isolation by faulting. It looks like the low regions to its south and north were faulted down and then covered by basalts, that were later dusted by crater ejecta; the two dark halo craters reveal the buried dark lavas. Now we only need to wonder why these areas faulted downward, and I've fresh out of speculations.<br /> | Nearly every piece of lunar terrain was formed by impact or volcanism, and has been modified by one or both of these processes. But the 50 km long, steep-sided plateau west of Eudoxus is strangely different from most impact and volcanic landforms. This is the northern end of the Caucasus Mountains and so is related to impact because it is apparently part of the rim of the Imbrium Basin. There appears to be a general lowering of topography toward Laméch, the 13 km crater at the eastern end of the plateau, consistent with it being ejecta on top of an uplifted rim. But what sculpted the sharply-defined sides of the plateau? It's possible (but just speculation) that the slightly curved western end is all that remains of a steeply-dipping crater such as Calippus, shown at the bottom edge of the image. The bright, south-facing scarp is similar to, and parallel to, the many faults that cut the Apennines and Caucasus. The hidden north side is more complex, bearing two straight-edged notches. I suppose this distinctive feature is really just an ejecta/rim block, and its peculiarity is due to its isolation by faulting. It looks like the low regions to its south and north were faulted down and then covered by basalts, that were later dusted by crater ejecta; the two dark halo craters reveal the buried dark lavas. Now we only need to wonder why these areas faulted downward, and I've fresh out of speculations.<br /> | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

<strong>Related Links</strong><br /> | <strong>Related Links</strong><br /> | ||

Rükl plate 13<br /> | Rükl plate 13<br /> | ||

| − | Click [http://www.lunar-captures.com/craters_A/080118_aristoteleseudoxus_tar.jpg | + | Click [http://www.lunar-captures.com/craters_A/080118_aristoteleseudoxus_tar.jpg here] to see George's full mosaic. <br /> |

<br /> | <br /> | ||

<strong>Note: You can leave comments on this LPOD by clicking on the"Discussion" tab above.</strong><br /> | <strong>Note: You can leave comments on this LPOD by clicking on the"Discussion" tab above.</strong><br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| − | <em>And you can support LPOD when you buy any book from Amazon thru [http://www.lpod.org/?page_id=591 | + | <em>And you can support LPOD when you buy any book from Amazon thru [http://www.lpod.org/?page_id=591 LPOD!]</em> |

</div> | </div> | ||

---- | ---- | ||

===COMMENTS?=== | ===COMMENTS?=== | ||

| − | + | Register, and click on the <b>Discussion</b> tab at the top of the page. | |

Revision as of 16:07, 11 January 2015

Lamech Plateau

image by George Tarsoudis, Alexandroupolis, Greece

Nearly every piece of lunar terrain was formed by impact or volcanism, and has been modified by one or both of these processes. But the 50 km long, steep-sided plateau west of Eudoxus is strangely different from most impact and volcanic landforms. This is the northern end of the Caucasus Mountains and so is related to impact because it is apparently part of the rim of the Imbrium Basin. There appears to be a general lowering of topography toward Laméch, the 13 km crater at the eastern end of the plateau, consistent with it being ejecta on top of an uplifted rim. But what sculpted the sharply-defined sides of the plateau? It's possible (but just speculation) that the slightly curved western end is all that remains of a steeply-dipping crater such as Calippus, shown at the bottom edge of the image. The bright, south-facing scarp is similar to, and parallel to, the many faults that cut the Apennines and Caucasus. The hidden north side is more complex, bearing two straight-edged notches. I suppose this distinctive feature is really just an ejecta/rim block, and its peculiarity is due to its isolation by faulting. It looks like the low regions to its south and north were faulted down and then covered by basalts, that were later dusted by crater ejecta; the two dark halo craters reveal the buried dark lavas. Now we only need to wonder why these areas faulted downward, and I've fresh out of speculations.

Chuck Wood

Technical Details

18 Jan. 2008, Newtonian 250mm at f/6.3, DMK 21AF04, filter Green; 5 images from 5 AVI files about 2300 frames each.

Related Links

Rükl plate 13

Click here to see George's full mosaic.

Note: You can leave comments on this LPOD by clicking on the"Discussion" tab above.

And you can support LPOD when you buy any book from Amazon thru LPOD!

COMMENTS?

Register, and click on the Discussion tab at the top of the page.