Difference between revisions of "July 16, 2004"

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

<table width="100%" border="0" cellpadding="8"> | <table width="100%" border="0" cellpadding="8"> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| − | <td><div align="center"><p>Image Credit: Apollo 17 Metric Camera Image M2444</div></td> | + | <td><div align="center" span class="main_sm"><p>Image Credit: Apollo 17 Metric Camera Image M2444</p></div></td> |

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

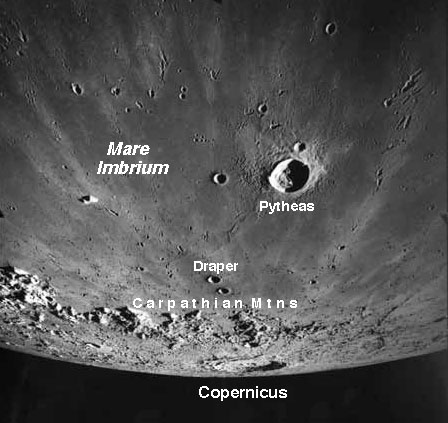

Rays and pits go hand in hand. The formation of crater rays was one of the totally misunderstood features on the Moon until Gene Shoemaker studied Meteor Crater in Arizona in the 1950s. He discovered that the impact event threw out streams of boulders and rocky blocks that gouged the surrounding surface and deposited material from beneath the crater onto the surface. He proposed exactly the same origin for lunar crater rays, an idea supported by his observation of small pits along Copernicus' rays crossing southern Mare Imbrium. This dramatic Apollo 17 view wonderfully displays both the bright rays and the secondary crater pits from Copernicus. The crater itself is obliquely viewed near the horizon about 400 km distant. Most of the elongated and overlapping small secondary craters are embedded in the light hued rays. But why are rays bright? In 1985, Carle Pieters (Brown University) and her colleagues showed that the bright ray material was highland rocks excavated by the impact of Copernicus. Highland materials are bright because they are made predominately of the light colored aluminum-rich mineral anorthosite. But, you should say, Copernicus impacted into the dark mare lavas of Mare Insularum. Yes, but the lavas are thin and they overly highland anorthosites! We are beginning to understand how the Moon works!</p> | Rays and pits go hand in hand. The formation of crater rays was one of the totally misunderstood features on the Moon until Gene Shoemaker studied Meteor Crater in Arizona in the 1950s. He discovered that the impact event threw out streams of boulders and rocky blocks that gouged the surrounding surface and deposited material from beneath the crater onto the surface. He proposed exactly the same origin for lunar crater rays, an idea supported by his observation of small pits along Copernicus' rays crossing southern Mare Imbrium. This dramatic Apollo 17 view wonderfully displays both the bright rays and the secondary crater pits from Copernicus. The crater itself is obliquely viewed near the horizon about 400 km distant. Most of the elongated and overlapping small secondary craters are embedded in the light hued rays. But why are rays bright? In 1985, Carle Pieters (Brown University) and her colleagues showed that the bright ray material was highland rocks excavated by the impact of Copernicus. Highland materials are bright because they are made predominately of the light colored aluminum-rich mineral anorthosite. But, you should say, Copernicus impacted into the dark mare lavas of Mare Insularum. Yes, but the lavas are thin and they overly highland anorthosites! We are beginning to understand how the Moon works!</p> | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| − | <p align="right" class="story">— [mailto:tychocrater@yahoo.com Chuck Wood]</p></ | + | <p align="right" class="story">— [mailto:tychocrater@yahoo.com Chuck Wood]</p></blockquote> |

| + | <p class="story" align="left"><b>Related Links: </b><br> | ||

| + | Hawke, B.R and others (2004) The origin of lunar crater rays. Icarus 170, 1-16.<br> | ||

| + | Pieters, C.M. and others (1985) The nature of crater rays: the Copernicus example. Journal of Geophysical Research 90, 12393-12413.</p> | ||

| + | <p class="story"><b>Tomorrow's LPOD:</b> Our Moon</p> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | </table> | ||

| + | <!-- start bottom --> | ||

| + | <table width="100%" border="0" cellspacing="2" cellpadding="4"> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td><hr></td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

Revision as of 20:34, 20 January 2015

Raisin Pits

Image Credit: Apollo 17 Metric Camera Image M2444 |

|

Raisin Pits Rays and pits go hand in hand. The formation of crater rays was one of the totally misunderstood features on the Moon until Gene Shoemaker studied Meteor Crater in Arizona in the 1950s. He discovered that the impact event threw out streams of boulders and rocky blocks that gouged the surrounding surface and deposited material from beneath the crater onto the surface. He proposed exactly the same origin for lunar crater rays, an idea supported by his observation of small pits along Copernicus' rays crossing southern Mare Imbrium. This dramatic Apollo 17 view wonderfully displays both the bright rays and the secondary crater pits from Copernicus. The crater itself is obliquely viewed near the horizon about 400 km distant. Most of the elongated and overlapping small secondary craters are embedded in the light hued rays. But why are rays bright? In 1985, Carle Pieters (Brown University) and her colleagues showed that the bright ray material was highland rocks excavated by the impact of Copernicus. Highland materials are bright because they are made predominately of the light colored aluminum-rich mineral anorthosite. But, you should say, Copernicus impacted into the dark mare lavas of Mare Insularum. Yes, but the lavas are thin and they overly highland anorthosites! We are beginning to understand how the Moon works! Related Links: Tomorrow's LPOD: Our Moon |

Author & Editor: Technical Consultant: A service of: |

COMMENTS?

Register, and click on the Discussion tab at the top of the page.