Difference between revisions of "April 20, 2013"

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

<!-- ws:start:WikiTextHeadingRule:0:<h1> --> | <!-- ws:start:WikiTextHeadingRule:0:<h1> --> | ||

<!-- ws:start:WikiTextLocalImageRule:6:<img src="http://lpod.wikispaces.com/file/view/LPOD-Apr20-13.jpg/424736718/LPOD-Apr20-13.jpg" alt="" title="" /> -->[[File:LPOD-Apr20-13.jpg|LPOD-Apr20-13.jpg]]<!-- ws:end:WikiTextLocalImageRule:6 --><br /> | <!-- ws:start:WikiTextLocalImageRule:6:<img src="http://lpod.wikispaces.com/file/view/LPOD-Apr20-13.jpg/424736718/LPOD-Apr20-13.jpg" alt="" title="" /> -->[[File:LPOD-Apr20-13.jpg|LPOD-Apr20-13.jpg]]<!-- ws:end:WikiTextLocalImageRule:6 --><br /> | ||

| − | <em>Lunar Orbiter 4 mosaic (left) from [http://planetarymapping.wr.usgs.gov/Target/project/3 | + | <em>Lunar Orbiter 4 mosaic (left) from [http://planetarymapping.wr.usgs.gov/Target/project/3 USGS], and Apollo 16-M2468 excerpt from [http://wms.lroc.asu.edu/apollo/view?image_name=AS16-M-2468 Apollo Image Archive]. P,L, S, I , R and D are Piazzi C,</em><br /> |

<em>Lacroix, Shickard, Inghirami A, Ritchey and Abulfeda D.</em><br /> | <em>Lacroix, Shickard, Inghirami A, Ritchey and Abulfeda D.</em><br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

are in the minority for lunar craters - they are primary impacts, created by a projectile from space smashing into the lunar surface. But sec-<br /> | are in the minority for lunar craters - they are primary impacts, created by a projectile from space smashing into the lunar surface. But sec-<br /> | ||

ondary craters are far more common than primaries. Just think of Copernicus; one 93 km wide crater surrounded by hundreds of secondaries,<br /> | ondary craters are far more common than primaries. Just think of Copernicus; one 93 km wide crater surrounded by hundreds of secondaries,<br /> | ||

| − | each typically smaller than a few kilometers in diameter. And there more be [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2006JE002817/abstract | + | each typically smaller than a few kilometers in diameter. And there more be [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2006JE002817/abstract millions] of secondaries with diameters of tens of meters. There<br /> |

are many more secondaries of large size than commonly recognized too. We can easily recognize that aligned and overlapping craters in the<br /> | are many more secondaries of large size than commonly recognized too. We can easily recognize that aligned and overlapping craters in the<br /> | ||

Rheita and Snellius valleys are secondaries from the Necataris Basin. But in addition, nearly 40 years ago US Geological Survey mapper Don<br /> | Rheita and Snellius valleys are secondaries from the Necataris Basin. But in addition, nearly 40 years ago US Geological Survey mapper Don<br /> | ||

| − | Wilhelms [http://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1976LPSC....7.2883W | + | Wilhelms [http://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1976LPSC....7.2883W warned us] that basin secondaries are widespread. For example, the left image, recreated from Don's paper, shows a variety of ejecta<br /> |

effects derived from the formation of the Orientale Basin; the crater marked S is Schickard. The Ori arrow points to the center of the basin and<br /> | effects derived from the formation of the Orientale Basin; the crater marked S is Schickard. The Ori arrow points to the center of the basin and<br /> | ||

crater chains and ridged deposits are clearly radial to the basin. Don argues that many of craters are also Orientale secondaries. Craters<br /> | crater chains and ridged deposits are clearly radial to the basin. Don argues that many of craters are also Orientale secondaries. Craters<br /> | ||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

from the point of view of observers, makes another goal - can primary and basin secondary craters be distinguished at the eyepiece?<br /> | from the point of view of observers, makes another goal - can primary and basin secondary craters be distinguished at the eyepiece?<br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| − | <em>[mailto:tychocrater@yahoo.com | + | <em>[mailto:tychocrater@yahoo.com Chuck Wood]</em><br /> |

<br /> | <br /> | ||

<strong>Related Links</strong><br /> | <strong>Related Links</strong><br /> | ||

Revision as of 17:03, 11 January 2015

Secondary Considerations

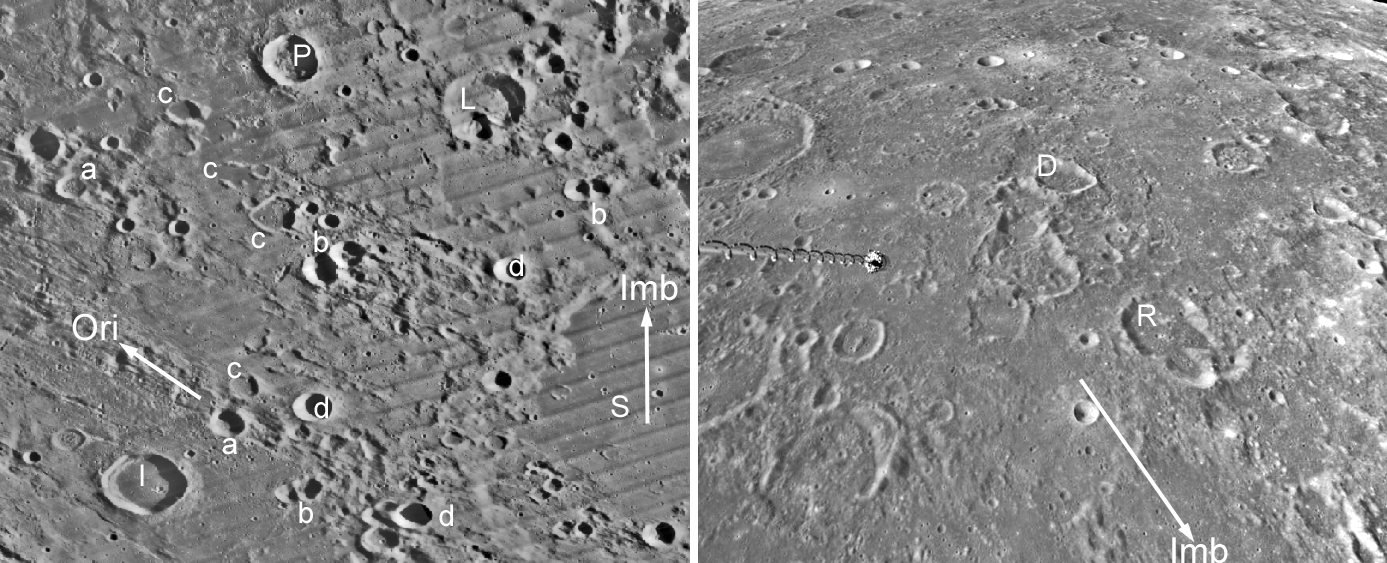

Lunar Orbiter 4 mosaic (left) from USGS, and Apollo 16-M2468 excerpt from Apollo Image Archive. P,L, S, I , R and D are Piazzi C,

Lacroix, Shickard, Inghirami A, Ritchey and Abulfeda D.

Hooray for Boston!

When we think of impact craters it is often of glorious features like Copernicus or small pinpricks of brightness like Linné. But both of these

are in the minority for lunar craters - they are primary impacts, created by a projectile from space smashing into the lunar surface. But sec-

ondary craters are far more common than primaries. Just think of Copernicus; one 93 km wide crater surrounded by hundreds of secondaries,

each typically smaller than a few kilometers in diameter. And there more be millions of secondaries with diameters of tens of meters. There

are many more secondaries of large size than commonly recognized too. We can easily recognize that aligned and overlapping craters in the

Rheita and Snellius valleys are secondaries from the Necataris Basin. But in addition, nearly 40 years ago US Geological Survey mapper Don

Wilhelms warned us that basin secondaries are widespread. For example, the left image, recreated from Don's paper, shows a variety of ejecta

effects derived from the formation of the Orientale Basin; the crater marked S is Schickard. The Ori arrow points to the center of the basin and

crater chains and ridged deposits are clearly radial to the basin. Don argues that many of craters are also Orientale secondaries. Craters

labeled a are well-formed secondary craters, those with a b are pairs of "secondaries whose rim intersections are straight septa", to quote Don.

Craters marked c are degraded or incomplete secondaries embayed by ejecta that travelled across the surface as surges. d craters may be

primary craters or possibly secondaries resulting from high angle ejection of debris. The south up image on the right is the area between Abul-

feda (top left) and Albategnius (off image to bottom right). Don proposes that many of the depicted craters are Imbrium Basin ejecta, including

the chain below Abulfeda D (probably a Nectaris secondary), and Ritchey (R) and its overlapping ears. Based on Wilhelms' work many craters

smaller than 30 km in diameter may be basin secondaries. Clearly this would affect inferred ages of features based upon crater counts, and

from the point of view of observers, makes another goal - can primary and basin secondary craters be distinguished at the eyepiece?

Chuck Wood

Related Links

Rükl plate 61 and 45

21st Century Atlas chart 24 & 13.