|

|

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) |

| Line 7: |

Line 7: |

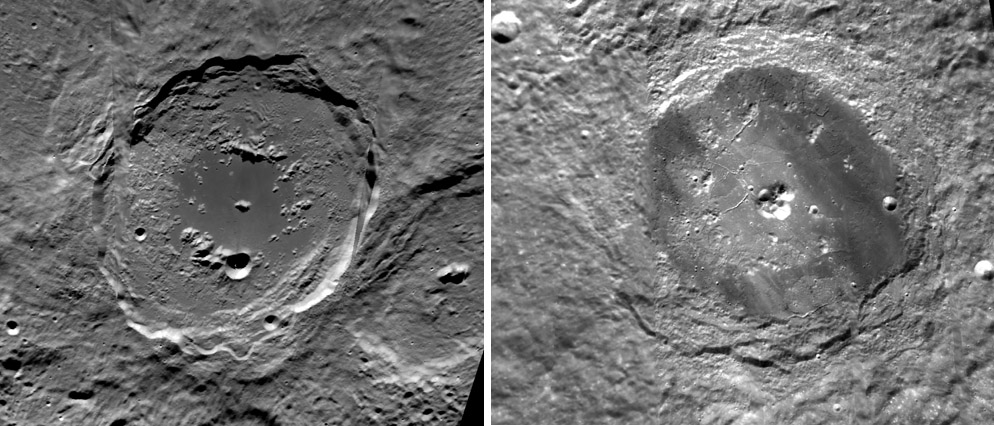

| | <p>[[File:Antoniadi-ComptonLPOD.jpg|Antoniadi-ComptonLPOD.jpg]]<br /> | | <p>[[File:Antoniadi-ComptonLPOD.jpg|Antoniadi-ComptonLPOD.jpg]]<br /> |

| | <em>Clementine images from USGS [http://pdsmaps.wr.usgs.gov/PDS/public/explorer/html/moonpick.htm Map-A-Planet]</em></p> | | <em>Clementine images from USGS [http://pdsmaps.wr.usgs.gov/PDS/public/explorer/html/moonpick.htm Map-A-Planet]</em></p> |

| − | <p>The Main Sequence of lunar craters is a systematic change in morphology from small bowl-shaped simple craters, to slump-walled complex craters, to terrace-walled complex craters to impact basins. In 1971 Bill Hartmann and I discovered two features on the luanr farside that are transitional between complex craters and basins. We named these structures central peak basins, because they have both the central peak of normal complex craters and an inner ring, like basins. Antoniadi (left) is a 143 km wide central peak basin with a small peak surrounded by an incomplete ring of peaks and hills with a diameter of 65 km. The area inside the ring is flooded with dark lavas and the moat between the ring and the rim is rough with debris. Compton (165 km diameter) is opposite from Antoniadi in that its moat is lava covered and the area inside the fragmentary ring is older, light-hued plains cut by various linear rilles. Compton’s central peaks are massive and its 80 km wide ring is defined by relatively small and widely spaced peaks. I always use the word <em>transmogrify</em> to describe the process whereby central peaks are replaced by basin inner rings. I use the word because it implies something mysterious and not well understood, which is exactly the case. Somehow the rebound energy that creates central peaks is more widely distributed so that a ring of peaks is produced. Since only two central peak basins have been detected on the Moon it must require a rare circumstance for both a central peak and a ring of peaks to form. But perhaps there are more transitional structures than we recognize: perhaps [http://www.lpod.org/?m=20060722 Clavius] (225 km), [http://www.lpod.org/?m=20061017 Hippachus] (150 km) and other large craters, which are partially filled with smooth plains material, have buried inner rings. And look at smaller craters such as [http://www.lpod.org/?m=20070211 Petavius and Langrenus] that have rough inner floors as if a ring were trying to form. The transition from central peaks to basin rings is still very poorly understood!</p> | + | <p>The Main Sequence of lunar craters is a systematic change in morphology from small bowl-shaped simple craters, to slump-walled complex craters, to terrace-walled complex craters to impact basins. In 1971 Bill Hartmann and I discovered two features on the luanr farside that are transitional between complex craters and basins. We named these structures central peak basins, because they have both the central peak of normal complex craters and an inner ring, like basins. Antoniadi (left) is a 143 km wide central peak basin with a small peak surrounded by an incomplete ring of peaks and hills with a diameter of 65 km. The area inside the ring is flooded with dark lavas and the moat between the ring and the rim is rough with debris. Compton (165 km diameter) is opposite from Antoniadi in that its moat is lava covered and the area inside the fragmentary ring is older, light-hued plains cut by various linear rilles. Compton’s central peaks are massive and its 80 km wide ring is defined by relatively small and widely spaced peaks. I always use the word <em>transmogrify</em> to describe the process whereby central peaks are replaced by basin inner rings. I use the word because it implies something mysterious and not well understood, which is exactly the case. Somehow the rebound energy that creates central peaks is more widely distributed so that a ring of peaks is produced. Since only two central peak basins have been detected on the Moon it must require a rare circumstance for both a central peak and a ring of peaks to form. But perhaps there are more transitional structures than we recognize: perhaps [[July_22,_2006|Clavius]] (225 km), [[October_17,_2006|Hippachus]] (150 km) and other large craters, which are partially filled with smooth plains material, have buried inner rings. And look at smaller craters such as [[February_11,_2007|Petavius and Langrenus]] that have rough inner floors as if a ring were trying to form. The transition from central peaks to basin rings is still very poorly understood!</p> |

| | <p>[mailto:tychocrater@yahoo.com Chuck Wood]</p> | | <p>[mailto:tychocrater@yahoo.com Chuck Wood]</p> |

| | <p><strong>Related Links:</strong><br /> | | <p><strong>Related Links:</strong><br /> |

| | <em>Clementine Atlas of the Moon</em> plates 16 & 141<br /> | | <em>Clementine Atlas of the Moon</em> plates 16 & 141<br /> |

| | Hartmann, WK and CA Wood (1971) [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/nph-basic_connect?qsearch=wood+hartmann+1971&version=1 Moon:Origin and Evolution of Multi-Ring Basins.] <em>The Moon 3</em>, 3-78.</p> | | Hartmann, WK and CA Wood (1971) [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/nph-basic_connect?qsearch=wood+hartmann+1971&version=1 Moon:Origin and Evolution of Multi-Ring Basins.] <em>The Moon 3</em>, 3-78.</p> |

| − | <p><b>Yesterday's LPOD:</b> [[February 24, 2007|A Peek At Some Peaks]] </p> | + | <p><b>Yesterday's LPOD:</b> [[February 24, 2007|A Peek at Some Peaks]] </p> |

| | <p><b>Tomorrow's LPOD:</b> [[February 26, 2007|Extreme Limb]] </p> | | <p><b>Tomorrow's LPOD:</b> [[February 26, 2007|Extreme Limb]] </p> |

| − | <!-- Removed reference to store page 2 -->

| |

| − | </em></div>

| |

| | </div> | | </div> |

| | + | <p> </p> |

| | + | <p> </p> |

| | + | <p> </p> |

| | <!-- End of content --> | | <!-- End of content --> |

| | {{wiki/ArticleFooter}} | | {{wiki/ArticleFooter}} |