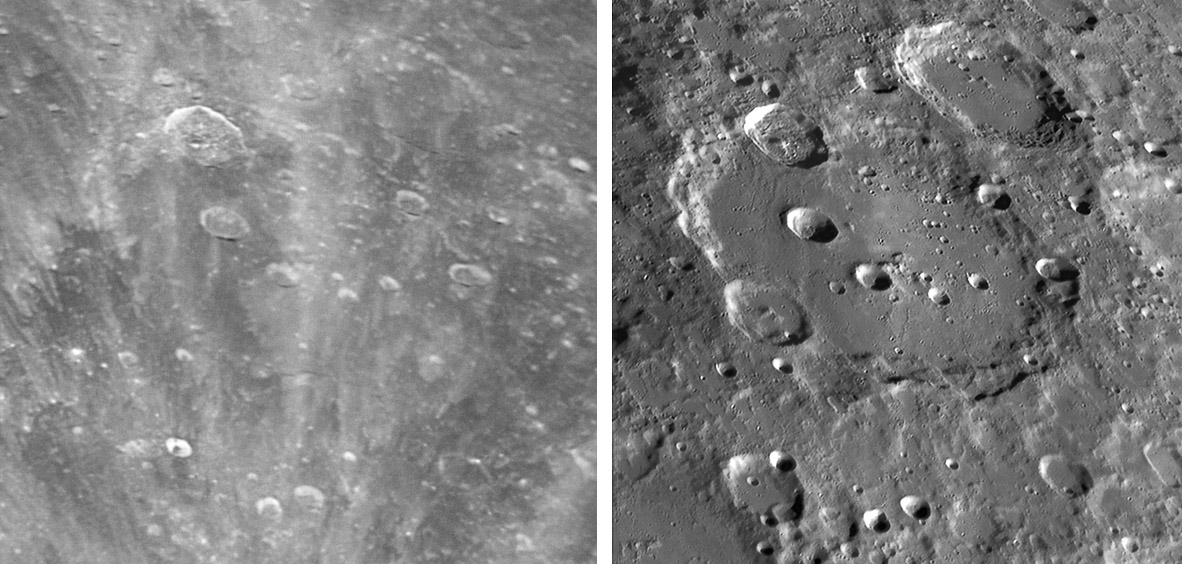

left image by Rainer Ehlert and right by Paolo Lazzarotti

Craters disappear when the Sun rides high over the Moon. In Rainer’s lunar noon view it is difficult to recognize the region at all, but a glance at Paolo’s early afternoon (lunar afternoon, that is) image of the same area instantly reveals the large and glorious crater Clavius. In comparing the two views it becomes apparent that at Full Moon craters are recognized where their inner rim scarps reflect the solar light back towards Earth. For all of the craters in Rainier’s image the upper (south is up) part of their rims are arcs of brightness, and the bottom parts mostly disappear, except where steep slopes cast thin crescentric shadows as at Clavius D. Craters such as Porter (on the north east rim of Clavius) disappear because their rims are narrow or not steep. The rays from Tycho also play over this area in intriguing ways. To the right and left of Clavius it almost looks like dark material has been streaked across the surface, but rays are bright highland debris and the dark areas are the zones not ray swept. Notice in Paolo’s image that the right (west) part of the floor is more heavily cratered than the east side. Then look at Rainer’s image and see that the west side is covered with Tycho’s rays (and presumably secondary craters). And note that the few small craters on the east part of the floor occur where there is a ray. Reading the history of the Moon is difficult, but using complementary views like these - which each contribute clues - makes it easier. So to get the full story, don’t ignore the bright Moon but take images of the same areas that you photograph when long shadows allure.

Technical Details:

Left: Nov 5, 2006. Takahashi Mewlon 250S @ 3000mm focal length + Lumenra Infinity 2-2M; capture software LuCam Recorder Pro v1.7, RegiStax v4 and Photoshop CS2. Multipoint alignment with 8 points and 50 images stacked from a movie of 500 in total.

Right: Sept 13, 2006. Gladio 315 Lazzarotti Opt. scope + Lumenera Infinity 2-1M camera + Edmunds Optics R filter; 200 of 4000 frames stacked.

Related Links:

Rükl plate 72

Rainer’s website

Paolo’s website

Entire image by Paolo

Yesterday's LPOD: Rilles Near Hase - My First Published Observation

Tomorrow's LPOD: A Southeast Backwater

COMMENTS?

Register, Log in, and join in the comments.